Herschel: The Slough Story

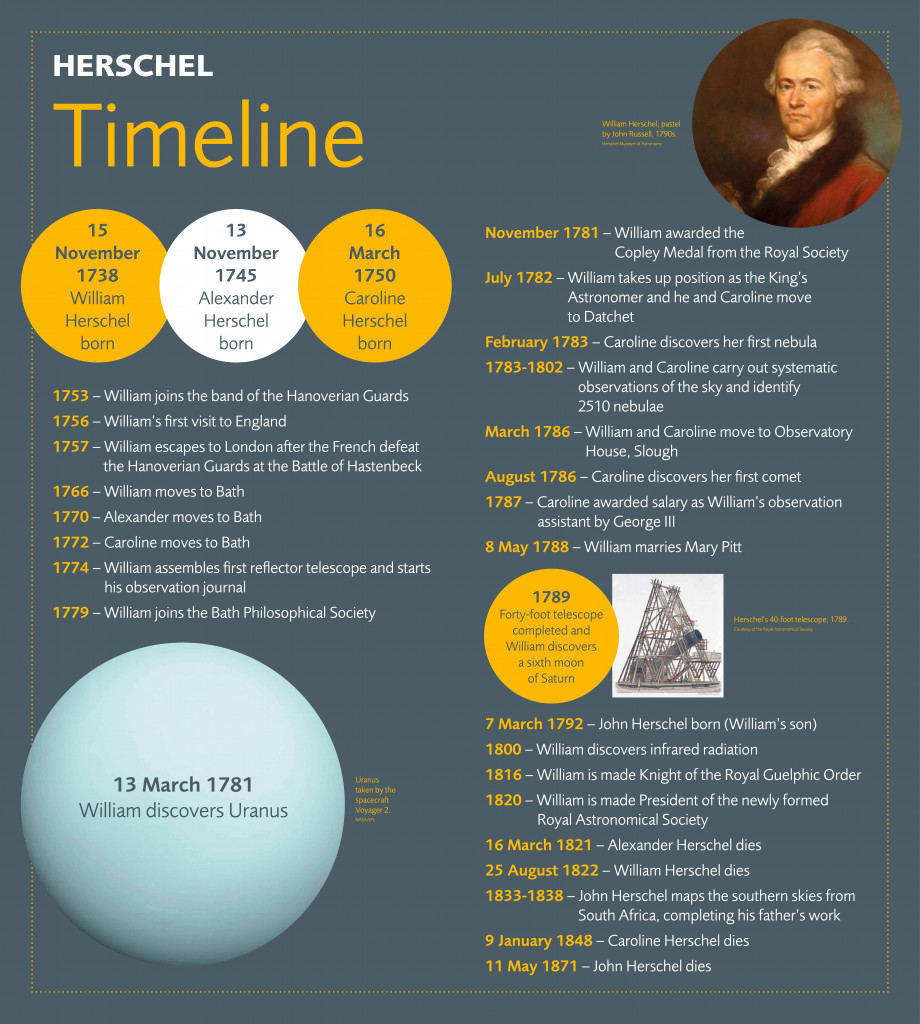

When William Herschel took up his position as the King’s Astronomer, he and Caroline left Bath to be near Windsor Castle. They eventually settled in Observatory House, Slough, on the corner of Windsor Road, now named Herschel Street. It was here that William remained for the rest of his life. He died on 25 August 1822 and is buried in St Laurence’s Church.

It was in the garden of Observatory House that William built his 40-foot telescope. For fifty years it was the largest telescope in the world and was so big it even featured on ordinance survey maps. It was dismantled on New Year’s Eve 1839. Observatory House was demolished in the late 1960s. The Herschel Sculpture, created in 1969 by artist Franta Belsky, now marks the former site of the house.

The Herschels’ legacy lives on in Slough, with a street, school, and doctor’s surgery bearing the family name. The Herschel Arms pub even depicts the landlord as William on its sign. Slough’s oldest green public space was renamed Herschel Park in 2001, and the design for Slough Bus Station was inspired by William’s discovery of infrared. The name and design of Observatory Shopping Centre are references to the Herschel family.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy however, away from the royal court and the cosmos, is that Slough continues to be a town of pioneers and innovators, a place where people discover, invent and create. A place where people – like William and Caroline – come from all over the world, to make their home.

Background image: Observatory House, Slough, 1924. Courtesy of the Royal Astronomical Society, RAS Photos 2. B6/68.